Optimizing low-latency trading systems

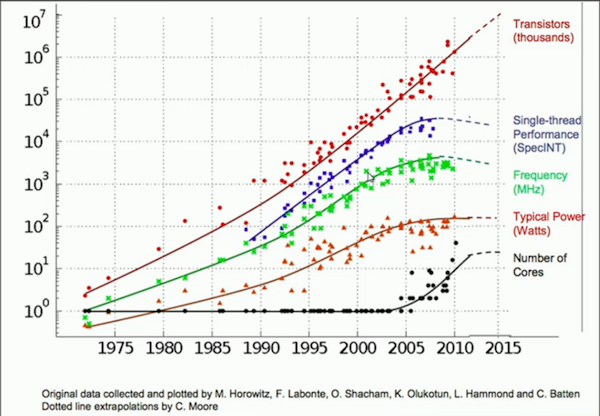

Modern hardware coupled with modern compilers allows software developers to write optimized programs with little effort. For this reason, developers are discouraged from micro-optimizing the source code by default. However, recent trends indicate that the growth in the general-purpose single-core performance has slowed down significantly, as can be observed in the figure below. As a consequence, there is now more pressure to optimize at the software layer. While compilers do help with most software optimizations, some areas require developers to open the hood to go above and beyond what compilers offer out of the box.

Source: Quora

Low-latency trading systems notoriously fit this particular narrative where micro-optimization is essential. The essentiality stems from the fact that these trading systems play economic games where the first to react takes it all. These games often involve taking advantage of the inefficiencies in the market to make near-instantaneous and low-risk trades. I highly recommend watching the below youtube video by Carl Cook to understand better how the optimizations of these systems differ from the more traditional ones.

In this post, I will discuss the core ideas behind some of the optimizations I have done as a part of a project to reduce the latency of a trading system we maintained. First, we try to identify specific areas where the compilers do not always generate the best code.

Cascading optimizations with Inlining

Compilers employ several optimization tactics, with inlining being the most critical optimization to consider in the context of low-latency trading systems. The Wikipedia page on inline expansion provides an excellent overview of the optimization for the uninitiated. A significant benefit of inlining is that it can enable other compiler optimizations. Consider the below code for instance.

void no_inline_init(int& value) __attribute__((noinline)) {

value = 42;

}

int write_no_inline() {

int value = 0xD;

no_inline_init(value);

return value;

}

void inline_init(int& value) __attribute__((always_inline)) {

value = 42;

}

int write_inline() {

int value = 0xD;

inline_init(value);

return value;

}There are two versions of the init function; one which the compiler always inlines and the other never. The two versions of the write functions call the corresponding init functions. Observe that in the inline version of the write function, after inline_init gets inlined by the compiler, the compiler can see that the variable value is being written to twice and optimizes out the first write completely. In contrast, the compiler does not have the same visibility in the non-inline version of the write call. We can verify the same by looking at the relevant parts of the generated assembly code below.

...

write_no_inline():

...

mov dword ptr [rsp + 4], 13

...

call no_inline_init(int&)

...

write_inline():

mov eax, 42

retGenerated using godbolt.org

However, inlining does not always result in a performance improvement, and thus the compilers use heuristics to determine where inlining is useful. As a result, compilers sometimes leave valuable latency improvements on the table. Hence, developers manually decide to always inline or never inline certain functions in the critical code path (also called fast path) and the non-latency-sensitive code path (also called slow path), respectively. The decision to do so involves extensive benchmarking. The below talk goes into more detail on the topic.

Please note that we cannot use Profile-Guided Optimizations (PGO) to help the compiler inline the functions better. In fact, PGO would optimize the slow path at the expense of the fast path since fast path events occur less often in comparison.

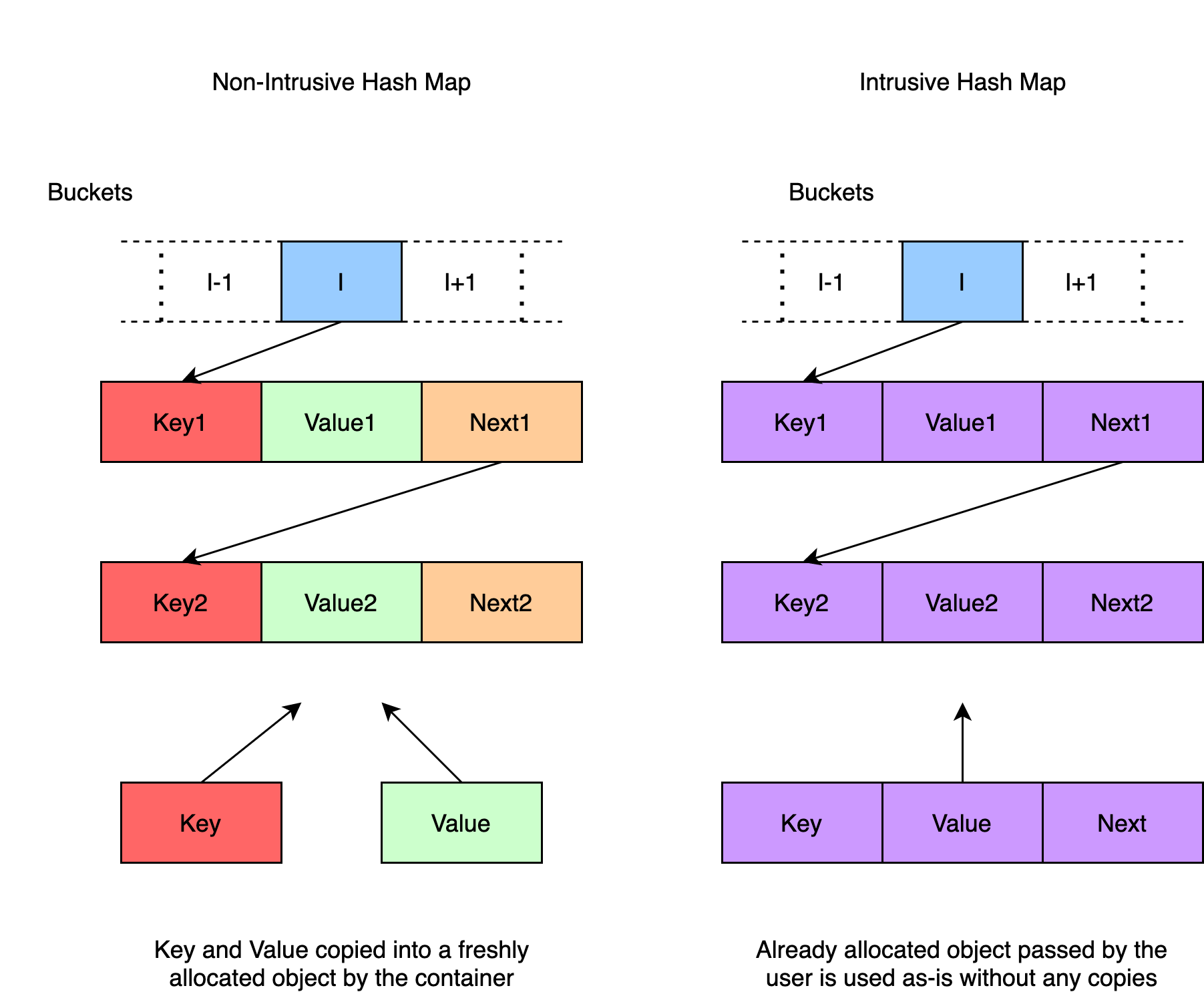

Unordered map insertion

Trading systems usually maintain their own versions of hash map implementation because intrusive containers leave memory management in the user’s control making them more performant than their non-intrusive counterparts. For the uninitiated, please check out Boost’s documentation on intrusive containers. See the figure below for a quick illustration of a diagrammatic comparison between intrusive and non-intrusive hash maps.

Generated using app.diagrams.net

Generated using app.diagrams.net

In our codebase, one common access pattern on the map is to check for the key’s existence, execute arbitrary logic and then insert the key into the map. See the code snippet below.

if (map.find(key) == map.end()) {

// key not found

state = ...

map.insert(make_intrusive_object(key, value));

} else {

// key found

state = ...

}There is a hidden inefficiency in the above code. The insert calls to map check for key existence. This existence check ensures that the user does not introduce duplicates into the structure. However, from the if condition, we already know that the key is not present in the map. Thus, we can avoid this redundant check by providing an insertUnsafe API that avoids traversing the linked list in search of a duplicate key. See the code below to get an understanding of the differences between both APIs

// Example intrusive object

struct Object {

int key, value;

Object* next;

};

// Retrieve hash table bucket

Object*& Map::get_bucket(Object* object) {

auto index = get_index(get_hash(obj.key));

return buckets[index];

}

// Simply insert object at the head of the linked list

void Map::insert_at_head(Object*& bucket, Object* object) {

object->next = bucket;

bucket = object;

}

// Traverse the bucket to figure out if the key already exists

bool Map::key_exists(Object*& bucket, Object* object) {

Object* current = bucket;

while (current != nullptr) {

if (current->key == object->key) {

return true;

}

current = current->next;

}

return false;

}

// This is the default version of the insert API

void Map::insert(Object* object) {

auto &bucket = get_bucket(object);

if (!key_exists(bucket, object)) {

insert_at_head(bucket, object);

}

}

// In this version of the API,

// the user must ensure that the key doesn't exist already

void Map::insert_unsafe(Object& object) {

auto &bucket = get_bucket(object);

insert_at_head(bucket, object);

}A quick look reveals that the insert API guards the user against a duplicate key insert while the insert_unsafe API does not. Avoiding the check not only saves us from traversing the list but also simplifies the control flow by having fewer branches. A linear control flow is beneficial to both the hardware and the compiler. At the hardware layer, we avoid unnecessary branch prediction, and at the compiler layer, a linear control flow is better suited for optimization.

Static vs dynamic dispatch

C++ virtual calls are expensive not only because of the indirect call but also because virtual calls prevent inlining. The compiler cannot inline a function whose address is only available at run-time. Moreover, this prevents other cascading optimizations being unable to inline code. The programmer can determine the static function type in specific scenarios where the compiler finds it challenging to infer the same. In such cases, using static_cast to dispatch to the static address of the function opens up inlining as a viable option for the compiler. Curiously recurring template pattern, CRTP for short, leverages the above concept. The code snippet below illustrates the difference between the two

// Conventional virtual call interface

class vBase {

public:

virtual void func() = 0;

};

class vDerived : public vBase {

void func() override {}

};

// CRTP

template <typename Derived>

class sBase {

public:

void func() { static_cast<Derived*>(this)->func(); }

};

class sDerived : public sBase<sDerived> {

public:

void func() {}

};When looking at the generated assembly code, you cannot find any indirect call in the CRTP case. Further, the function is inlined and optimized out.

Conclusion

Although individually these are minor optimizations, in combination, they can reduce the latency of the trading systems by a noticeable amount. Even a sub-microsecond latency reduction can make a difference on who wins the first-come-first-serve economic game. For this reason, even though the developers are still in the business of optimizing the software, using custom hardware via FPGAs is becoming increasingly popular in this space.