x32 ABI and optimizing memory-intensive applications

Recall that a hash map, also called an unordered map, is implemented using a hash table data structure. The hash table data structure is simply an array that is indexed by keys which typically go through a hash function. These indices potentially collide, and chaining is a common way to handle these collisions. Each element of the hash table array is a linked list, and the collisions are resolved by simply appending the key-value pair to the linked list forming a bucket. The idea here is that there are a constant number of items in the bucket on average, ideally not more than one, and that property results in constant-time lookup, insert and delete operations on the map.

Source: Hash table Wikipedia

Source: Hash table Wikipedia

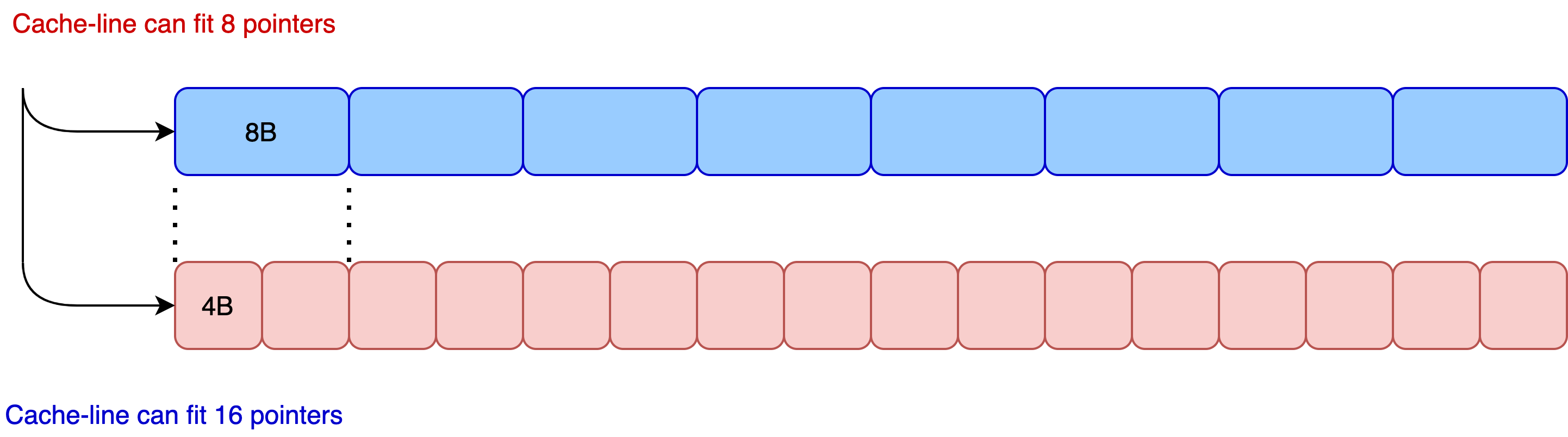

Most operations on a map involve fetching the bucket from memory. So how many buckets would fit in a cache line? A modern Intel x86-64 CPU has 64-byte cache lines and 8-byte pointers resulting in 8 pointers to buckets in a cache line. On the other hand, the i386 pointers are only 4 bytes in size, fitting in as many as 16 pointers which is twice the number. Having smaller pointers not only decreases the memory footprint, but it also leads to a more efficient usage of the cache. These improvements are advantageous since many applications require less than 4GiB of memory to run.

Generated using app.diagrams.net

Generated using app.diagrams.net

However, applications cannot simply use a 32-bit architecture since when the hardware runs in 32-bit mode, no other 64-bit applications can run on the same machine. Moreover, a 64-bit architecture has several other advantages over a 32-bit intel architecture. To get the best of both architectures, the linux kernel introduced a new architecture called x32 ABI. x32 ABI enables applications that require less than 4GiB of memory to run with less memory footprint and better cache utilization.

x32 ABI

Let us try to analyze the advantages of x86-64 from the introductory paragraph of the wiki page on x32 ABI.

The x32 ABI is an application binary interface (ABI) and one of the interfaces of the Linux kernel. It allows programs to take advantage of the benefits of x86-64 instruction set (larger number of CPU registers, better floating-point performance, faster position-independent code, shared libraries, function parameters passed via registers, faster syscall instruction) while using 32-bit pointers and thus avoiding the overhead of 64-bit pointers.

CPU registers

There are 8 more integer registers and another 8 more SSE registers in x86-64 in comparison to i386. Having more registers is beneficial since the compiler can then allocate more registers for working memory and register memory is orders of magnitude faster than the main memory or DRAM memory.

// a and b are registers

a*b + a%bThe above expression cannot be evaluated with just 2 registers as-is. If the compiler had no additional registers to work with, the compiler had to resort to using the stack memory for storing intermediate results. Since certain memory accesses could be avoided with additional registers, x86-64 leaves more room for optimization to the compiler.

Parameter passing

Since functions can be called across modules, compilers need to establish conventions on how to call a function. A proper convention must include

- how parameters are passed

- where to expect the return value

- what registers must be preserved and what can be overwritten

See the wikipedia page on the topic for more information. For our purposes, it is sufficient to notice that the parameters are pushed onto the stack in the 32-bit architecture, as shown below.

+------------+ |

| arg 2 | \

+------------+ >- previous function's stack frame

| arg 1 | /

+------------+ |

| ret %eip | /

+============+

| saved %ebp | \

%ebp-> +------------+ |

| | |

| local | \

| variables, | >- current function's stack frame

| etc. | /

| | |

| | |

%esp-> +------------+ /Source: Sorav Bansal’s OS lecture notes

On the other hand, in the more recent architectures, registers are used to pass the first few parameters to reduce the number of memory accesses. According to the wikipedia page on calling conventions, the System V ABI requires that,

The first six integer or pointer arguments are passed in registers RDI, RSI, RDX, RCX, R8, and R9, while XMM0, XMM1, XMM2, XMM3, XMM4, XMM5, XMM6 and XMM7 are used for floating point arguments … additional arguments are passed on the stack and the return value is stored in RAX.

Floating-point performance

For the uninitiated, SSE, also called Streaming SIMD Extensions, instruction set executes the same instruction on multiple data objects simultaneously. Since these objects are organized contiguously as a mini-vector, these instructions are alternatively called vectorized operations. This simultaneous processing has increased throughput since multiple operations of the same type are executed in the same cycle. The program, however, should be structured in a way to take advantage of the instruction set. x86-64 introduced the SSE instruction set for floating-point numbers for better throughput. Let us explore vectorized operations with the help of an example - computing the dot product of two 2-D points.

struct Point {

float x, y;

};

float dot_product(Point p0, Point p1) {

return p0.x * p1.x + p0.y * p1.y;

}Looking at the code, we can infer that the expressions p0.x * p1.x and p0.y * p1.y are amenable to vectorized multiplication since

- data members x and y are contiguous in memory, forming the mini-vector discussed above

- the operation is of the same type, i.e. multiplication

As expected, the compiler vectorizes the multiplication step, as can be seen from the assembly code generated below

dot_product(Point, Point): # @dot_product(Point, Point)

mulps xmm0, xmm1

movaps xmm1, xmm0

shufps xmm1, xmm0, 85 # xmm1 = xmm1[1,1],xmm0[1,1]

addss xmm1, xmm0

movaps xmm0, xmm1

retGenerated using godbolt.org

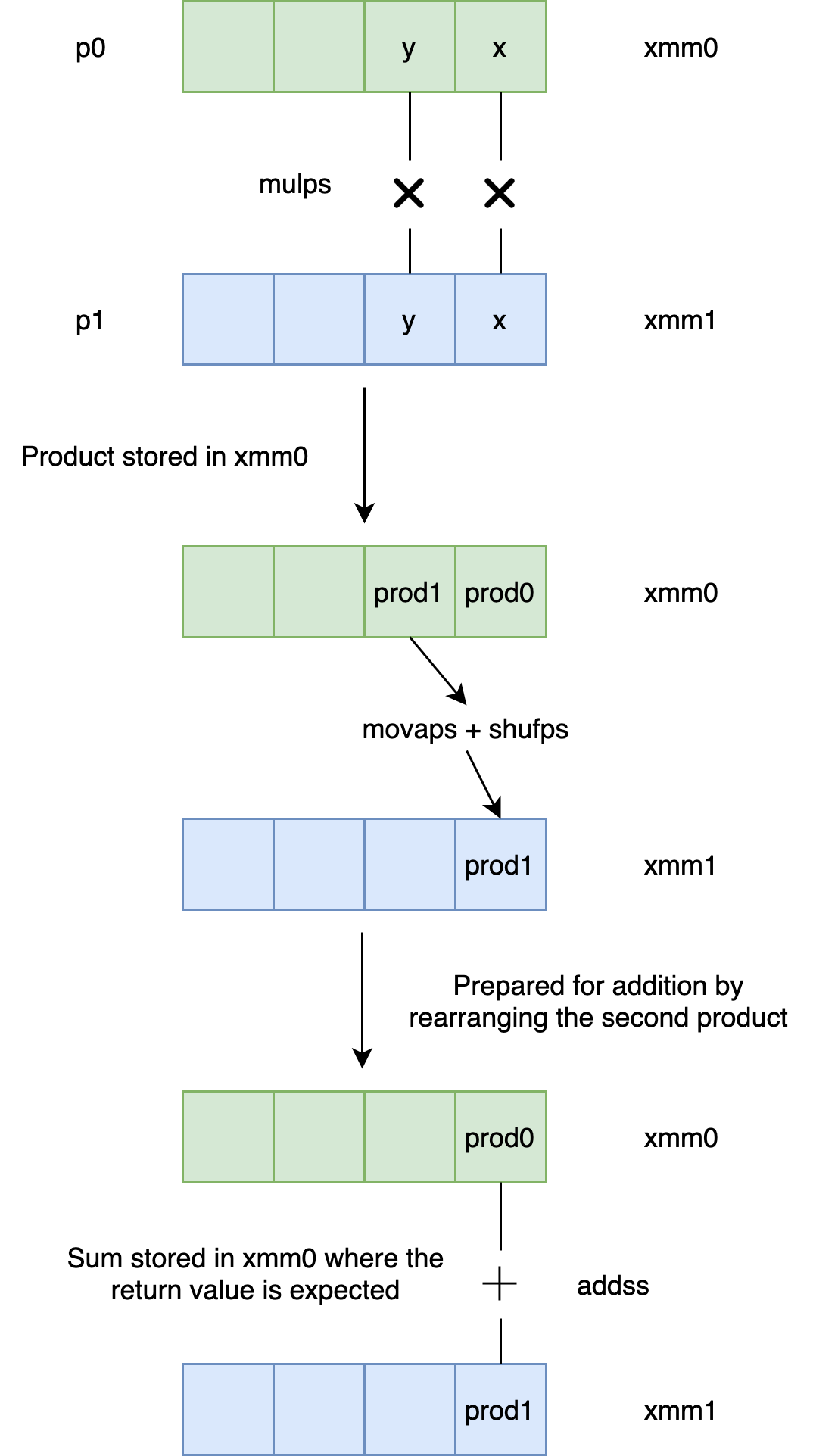

The initial instruction mulps does the vector multiplication part, which we have been discussing. The next two instructions, movaps and shufps prepare for the addition of both the products by rearranging the second product position. The next instruction, addss sums the products. The control flow is illustrated in the below figure

Generated using app.diagrams.net

Generated using app.diagrams.net

Similar to how integers are returned in rax, floating-point values are returned in xmm0.

System Calls

Modern intel 64-bit architectures provide a better system call mechanism than the older architectures based on 32-bit. This blog post provides a comprehensive overview of the significant differences between both the mechanisms. Let us try to understand why the modern system call API is more performant.

Renumbering of the system calls

System calls are renumbered to assign the more frequently used system calls lower numbers. Also, the system calls that are often used together appear together for a more optimized usage of the cache-line.

Less indirection

The syscall instruction entails less indirection than the int 0x80 instruction since in the case of an interrupt, the hardware is supposed to fetch the interrupt descriptor corresponding to the system call from the interrupt descriptor table. On the other hand, in the case of syscall instruction, the system call function address is already available in the MSR registers.

The sysenter instruction also involves more indirection than the syscall instruction. sysenter is never directly called by the application program, but instead, the application program calls a vDSO function __kernel_vsyscall to account for any changes in the user-kernel interface. No such calls are required in the case of sysenter since the instruction saves the return address to rcx, which is not the case for the sysenter instruction.

More registers

Having more registers in x86-64 architecture allows the kernel to minimize the usage of the user-stack. For instance, as seen before, the return address is now stored in rcx. Otherwise, the return address needs to be retrieved from the user stack. The performance of data retrieval from the user stack is exacerbated by the mode switch from user-mode to kernel-mode.

PIC and Shared libraries

PIC-based shared libraries are faster in the 64-bit mode than the 32-bit counterpart because of the introduction of RIP-relative addressing instructions in the newer architectures. Full details will not be covered in this post. However, I recommend reading this series of posts by Eli Bendersky

- Load-time relocation of shared libraries

- Position Independent Code (PIC) in shared libraries

- Position Independent Code (PIC) in shared libraries on x64

See the section on Performance implications in the last post of the series to better understand the differences.

Building Applications

While I am pretty excited about the x32 ABI, I am yet to see it being used in a production-grade application. I imagine the reason being my limited exposure coupled with the fact that the architecture is not supported out of the box in major distributions. Often, the kernel requires a recompile, and the user needs to specify an x32 specific command-line option when booting the kernel. However, I did see the concept of 32-bit pointers being used in the applications as a workaround. This workaround allows applications to leverage some of the advantages of the lower memory footprint of 32-bit pointers in a 64-bit application, albeit with additional application-layer code.

Memory Pool

Low-latency trading systems often maintain their own versions of memory allocators to reduce the number of system calls. The ideal scenario in these systems would be to pre-allocate all the memory required in the critical path at the start of the application. These trading systems lock all the memory accessed in the critical path to avoid any page replacement by the OS while quickly reacting to market data. The reaction times are in the ballpark of a few microseconds, and any disk access during this process will result in a lost trade. The production systems have large amounts of physical memory installed to accommodate this pre-allocation. A famous memory allocator used is the memory pool. There are several resources online explaining the concept. For example, take a look at this post.

Things to note

- Blocks are allocated using the

mmapsystem call and notmalloc. This method allows the memory pool to allocate at page boundaries and allocate huge pages instead of regular pages. Huge pages have shorter page walk times and levy less pressure on the TLB cache. - Chunk Size must be a multiple of pointer size since otherwise, it is not possible to reinterpret the data as a pointer for the free list.

Trading systems maintain a 32-bit pointer variation of the memory pool. A typical implementation involves maintaining a base pointer off which 32-bit offsets are calculated and represent the pointers corresponding to the memory pool.

// 32-bit pointers

template <typename T>

struct MiniMemoryPool {

static MiniMemoryPool* g_miniMemoryPool = nullptr;

// singleton pattern

static MiniMemoryPool* getInstance() {

if (g_miniMemoryPool) {

return g_miniMemoryPool;

}

g_miniMemoryPool = new MiniMemoryPool(...);

}

struct Ptr {

unsigned offset;

T& operator*() {

// add offset to base

return *static_cast<T*>(

static_cast<char*>(getInstance().getBase()) + offset

);

}

};

Ptr allocate() {

...

}

...

};The allocate function above is similar to the allocate function of a typical memory pool, except the offset is computed off of the base and returned wrapped in a Ptr object. Dereferencing the Ptr object fetches the object from memory by adding the offset to the base, as seen in the operator* implementation of Ptr. Note that the behaviour is undefined if the offset becomes larger than what can be fit in 32 bits, i.e. 4GiB.

Handling pointer overflows

As discussed above, the difference between base and offset could potentially overflow 32 bits. How does an application handle such overflows?

Reject allocations

A simple behaviour is to reject allocations that result in offsets that overflow 32-bits. Note that this does not mean that future allocations are impossible since the free list could be populated again, allowing for further allocations.

Coordinate across mini-memory pools

The system call mmap returns a kernel-chosen address when the first argument to the call is NULL. Instead, try specifying the addresses yourselves so that the addresses across memory pools have no overlap. This mechanism avoids gaps in the allocation of blocks from the same memory pool, thus keeping the offsets as low as possible.

Conclusion

When your application is amenable to x32 ABI, you can gain decent memory and potentially performance savings by switching architectures. On the other hand, if x32 ABI is not viable either because the OS distribution you use does not support the architecture or because you do not want to be limited by the 4GiB memory constraint, do not lose heart. You can still leverage the advantages of using 32-bit pointers by maintaining making some minor changes to your custom memory pool.