Minimizing redundant network reads

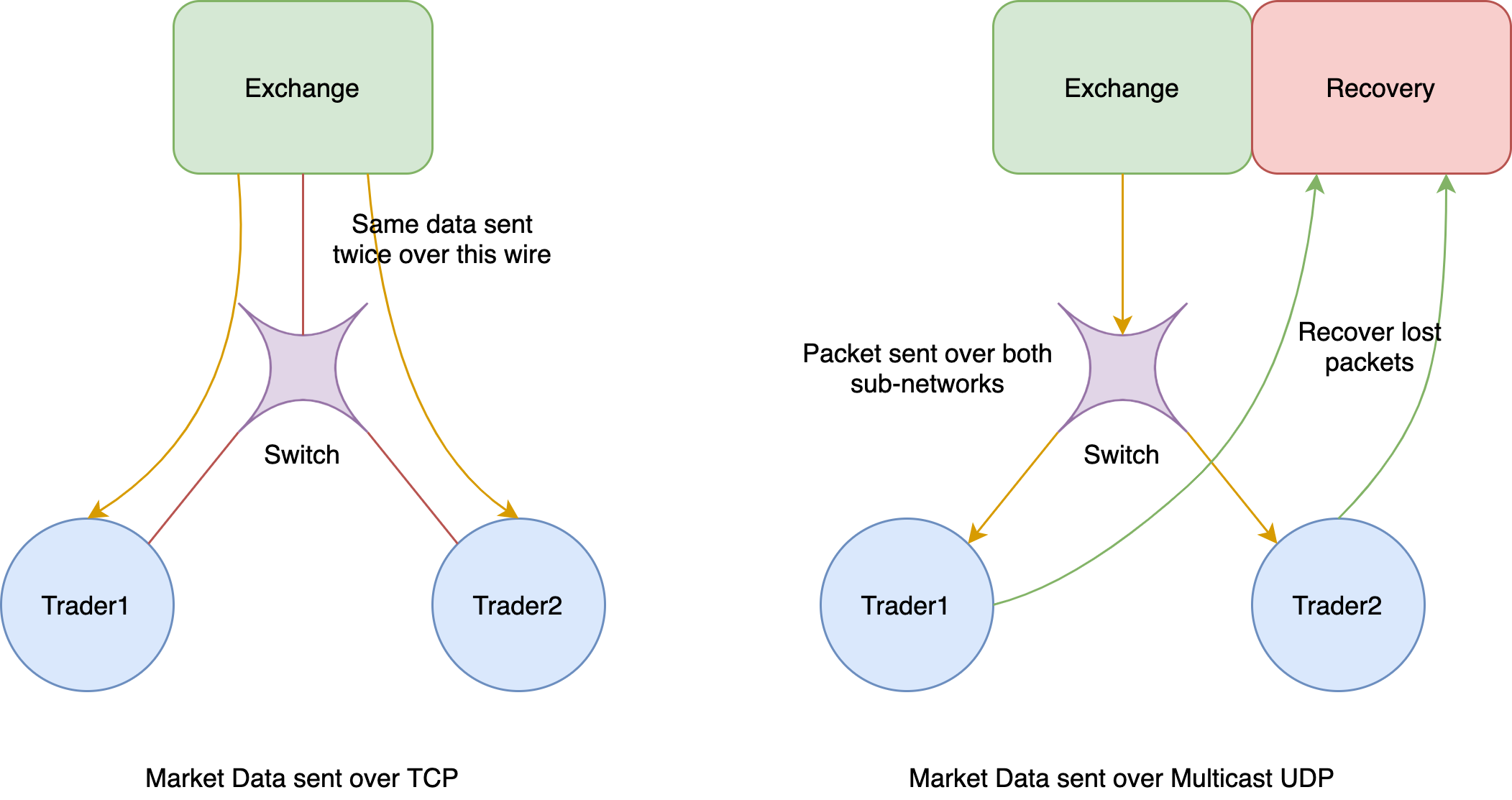

In the context of trading, the market data represents the state of the exchange. The data provides information related to the currently available orders on the exchange for each security. This data is common to all trading clients connected to the exchange. For this reason, maintaining a TCP connection with each client is expensive since the same data would then be redundantly sent over the network to each client, thus hogging the bandwidth. Hence, stock exchanges typically send market data over multicast UDP. The UDP protocol is not reliable, however. The exchanges provide a recovery service through which clients can request the dropped packets over a more reliable connection backed by TCP. These connections are rate-limited, however, since the exchange does not expect too many packet drops.

Packet sniffing

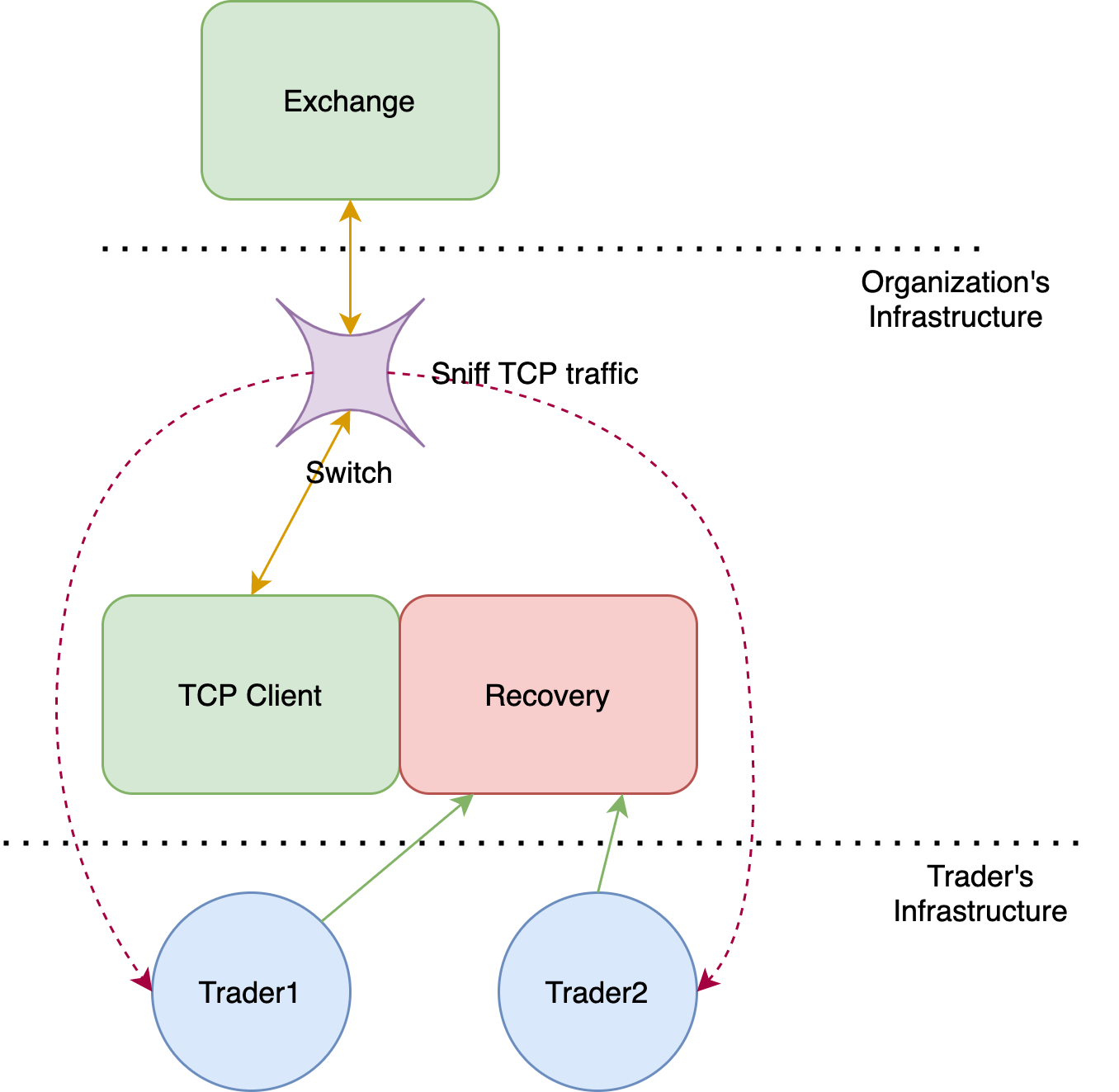

Not all stock exchanges adopt this particular model despite the apparent benefits of disseminating market data over UDP. In China markets, for example, the exchanges have strict compliance requirements and thus require TCP connections. However, compliance is required at the organization level and not at the application level. Since a single organization has multiple trading clients, we need some way to disseminate the data to applications internally. Creating a connection for each application simply does not scale, given that an organization potentially deploys 100s of trading strategies to production. Instead, organizations typically deploy a single TCP client that connects to the exchange. They also configure the switch to sniff all the TCP packets the client receives from the exchange. These sniffed packets are then disseminated to all the interested clients. For the recovery of lost packets, organizations deploy recovery servers internally.

Host-level read redundancy

Although we discussed several mechanisms to reduce bandwidth usage at the network level, none of them reduce read redundancy at the host machine level. A production machine, which is an end-point of the above-mentioned network links, typically hosts several applications that read the same market data. Creating a network socket for each application is wasteful since the same network data needs to be redundantly copied into each application’s memory. The NIC goes through the PICe bus to write the network packet into application’s memory address space. These redundant PCIe transfers end up being the bottleneck of the system.

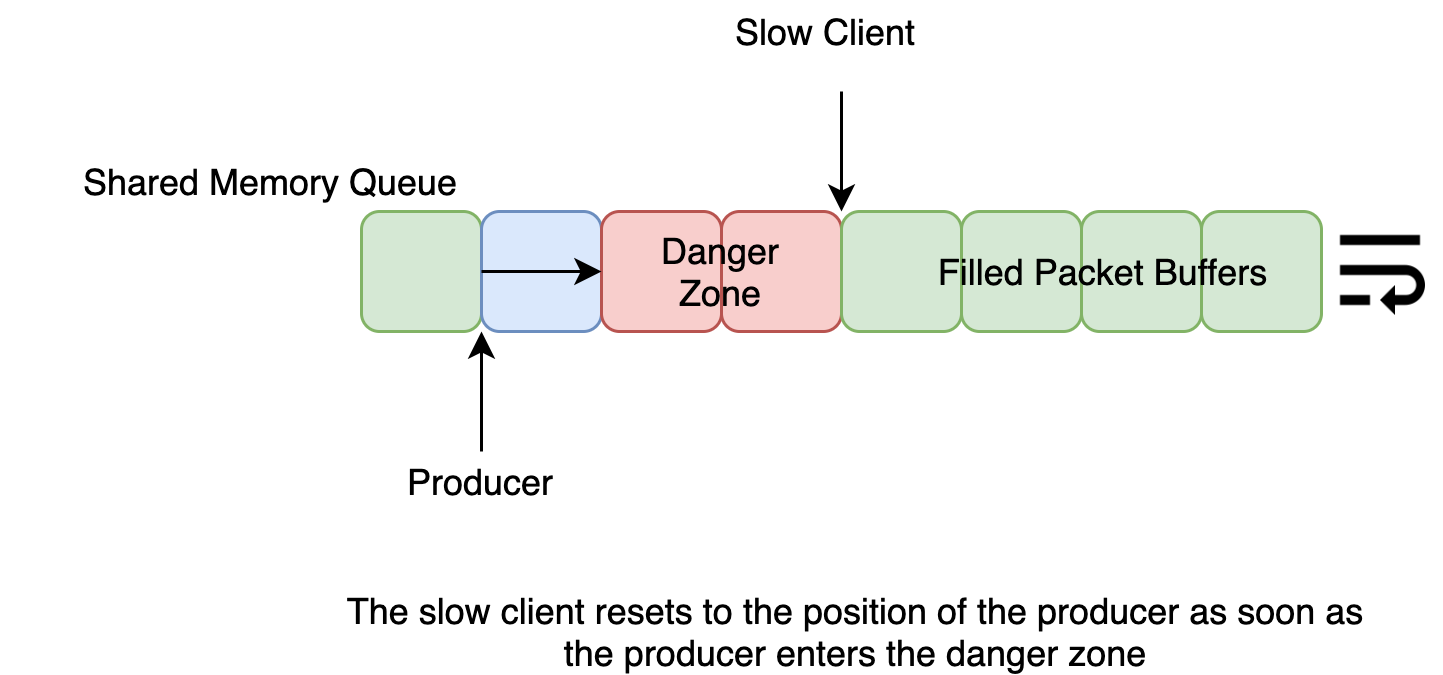

One solution to the above issue is to maintain a dedicated process whose sole purpose is to read network data and copy it into shared memory queue. The interested processes can then read the network packets from this shared memory. In the interest of keeping up with the incoming network traffic as well as in the interest of performance, the dedicated process does not wait for the slowest reader to read all the packets. For this reason, slow readers need to handle the queue wrapping around too fast.

The slow clients are recommended to reset their queue head to the current tail when they detect that they are falling behind the network traffic flow rate. When the producer is only a few packets away from overwriting the packet being read, the consumer drops all the remaining packets currently buffered in the queue. The correct state of the market can later be retrieved from the recovery server. Despite using caution, sometimes it just so happens that the producer was too quick to overwrite a reading packet. Such packets are dropped because the checksums do not match and hence the lack of synchronization between the producer and the consumers is hardly ever a correctness issue.

The proposed solution still faces a few drawbacks

- We need to reserve a dedicated core to run the producer-process. The process cannot share the core with other processes since it needs to keep up with the network ingress.

- The producer-process copies packets from the DMA (direct memory access) backed memory to the shared memory and copying is not free.

Let us explore an alternative shared memory solution where we address these challenges.

Asynchronous I/O interface

Before discussing the solution, it helps to understand the common I/O interface for user-space networking. The interface resembles that of the io_uring API introduced in Linux. A lot of the concepts carry over to this domain. Let us discuss this I/O mechanism briefly. To begin with, as the name suggests, there are no system calls in the critical path. All the read operations occur in the user-space. Moreover, the network read API is closer to the readv system call than the read system call in that the user submits several memory buffers at once. These memory buffers are filled with one datagram each. This style of a read is also called scatter input since the datagrams are not necessarily contiguous but are instead “scattered” into these memory buffers. The no-system call API is similar to kernel-polled version of the io_uring API. However, unlike in io_uring, the memory buffers are not submitted to the kernel but instead they are submitted to the NIC or more accurately, the software interface provided by the network device’s library.

Another difference between the user-space interface and that of the io_uring is that the network link is not identified by a file descriptor in the former. Instead, the applications create virtual NICs called queue pairs. A queue pair is configured at startup to control the network flow through the virtual NIC similar to how a socket in configured. In the current context, the queue pair is configured to send an IGMP request to subscribe to the appropriate multicast group and add appropriate multicast filters to listen only to the required groups.

Avoiding the extra copy

Now that we understand how the NIC transfers ethereum frames to the memory buffers, there is a seemingly straightforward solution that avoids the additional copy. We can share the memory buffers submitted to the NIC across the interested applications. However, before we can do this, we still need to flesh some details out.

Who submits these buffers? We still use a separate dedicated application to submit the buffers in shared memory. Then, how is this solution different from processing requirements? The main difference is that in this solution, the dedicated application need not poll for incoming network data. It can still submit the memory buffers asynchronously without the need to hog a processor core. How do the trading clients know when the data arrives over the buffer? Does each client maintain a completion queue of their own? No, only a single completion queue exists per network flow. The first few bytes of each memory buffer is initialized with a magic number before it is submitted to the queue pair. Since the write to the buffer is atomic, the clients detect arrival of new data by comparing the first few bytes with the magic number. This trick would not have been possible if the datagrams were arranged contiguously in memory instead of as memory buffers. Moreover, since the buffers are aligned at the cache line boundary, the reads are a bit faster. The reads are faster because unlike in the popular depictions of DMA, the network data reaches the cache before it reaches the main memory.

The current solution is not strictly better than the proposed solution earlier. The number of memory buffers you can register with NIC is very limited in comparison to the the amount of shared memory you can copy datagrams into. This is especially important for slow clients since some clients may not be able to keep up with the network ingress. The good news is that the first solution is sufficient in most cases for such clients.

Conclusion

When discussing about reducing read redundancy at the network layer, the choice is clear - use multicast whenever possible. However, when discussing shared memory solutions to reduce read redundancy across applications of a single host machine, we need to evaluate the latency requirements carefully.